SWOT Analysis Limitation: Why It Fails Without Strategic Context

SWOT only analyzes one thing. The risk is choosing the wrong thing. Learn why SWOT needs Wardley Mapping to show you where to aim your analysis.

Commentary Details

What Is SWOT Analysis? A Simple Tool With a Hidden Problem

SWOT analysis is a strategic planning framework that evaluates four factors: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats.

Strengths and Weaknesses are internal—things you control. Opportunities and Threats are external—things happening around you. Put these in a 2x2 matrix, fill in the boxes, and you have a strategic assessment.

That's the theory.

In practice, SWOT asks you to analyze something. A product. A market position. A capability. An initiative. But here's the question SWOT never answers: which something?

SWOT analyzes one thing. The risk is choosing the wrong thing.

Why SWOT Is Popular (and Why People Trust It)

SWOT dominates strategic planning for good reasons.

Simplicity. Anyone can draw a 2x2 matrix. You don't need complex software or years of training. Just four boxes and honest assessment.

Collaboration. SWOT encourages team discussion. Different perspectives fill different boxes. The process brings people together around a shared problem.

Universality. SWOT works across industries and contexts. Product teams use it. Marketing teams use it. Executive teams use it. It's familiar territory.

Cultural familiarity. SWOT is embedded in MBA programs, consulting frameworks, and business literature. When you suggest SWOT, everyone knows what you mean. No explanation required.

These strengths explain why SWOT remains widely used in 2024–2025, despite criticism. The tool itself isn't broken. But it's incomplete.

The Real Limitation of SWOT

SWOT only analyzes one thing. The risk is choosing the wrong thing.

Imagine you're running SWOT on your entire company. You list company strengths. Company weaknesses. Market opportunities. Competitive threats. The matrix fills up. You feel productive.

But you've analyzed the company as if it's one uniform thing. That's rarely true.

Your company has multiple products, multiple markets, multiple capabilities, multiple competitive positions. Each has different strengths, different weaknesses, different opportunities, different threats.

A SWOT on "the company" hides this complexity. It creates the illusion of strategic clarity while avoiding the real question: which part of your company matters most right now?

This is the core limitation. SWOT tells you how to analyze. It doesn't tell you what to analyze.

Or, more simply:

SWOT is a lens. A powerful lens. But lenses only show you what you point them at. If you're pointing at the wrong thing, no amount of analysis will help.

Why Leaders Secretly Worry About SWOT

Here's what consultants and directors don't say out loud: SWOT feels productive, but it often produces slides that look smart while hiding the real questions.

The wrong product problem. You spend three hours SWOTting Product A. Meanwhile, Product B is the one that needs attention. You've analyzed the right things about the wrong product.

The region mix-up. Your team SWOTs the North American market. But your growth opportunity is in Asia-Pacific. You've built a beautiful strategic document for the wrong geography.

The capability blind spot. You SWOT your marketing team. But the real constraint is your operations capability. You've optimized the wrong function.

The political risk. Someone important suggested focusing on Initiative X. You SWOT it because saying no feels risky. Six months later, you realize Initiative Y was the real priority. Now you've wasted resources and lost credibility.

The misdirection risk. Your SWOT looks impressive in the boardroom. Executives nod along. But you've analyzed something that doesn't actually matter to your strategic position. You've created clarity about the wrong thing.

These fears aren't theoretical. They're the quiet conversations happening after strategy meetings. "Did we analyze the right thing?" "I'm not sure this SWOT helped." "I wish we'd looked at X instead."

SWOT doesn't cause these problems. It just doesn't prevent them.

What SWOT Gets Right — When Used Correctly

SWOT isn't wrong. It's powerful when aimed correctly.

A well-focused SWOT reveals critical insights. When you know exactly what to analyze, SWOT gives you a systematic way to assess it.

Micro-example one: Your team decides to SWOT your customer support capability specifically. You identify that your strength is speed (fast response times), your weakness is depth (can't handle complex technical issues), your opportunity is automation (chatbots can handle routine questions), and your threat is competition (rivals are investing in superior support). This SWOT helps. You've analyzed something specific with clear boundaries.

Micro-example two: You SWOT a new product launch in the European market. Strengths: strong brand recognition. Weaknesses: no local distribution partners. Opportunities: growing demand for your product category. Threats: strict regulatory requirements. This SWOT is actionable because the scope is clear.

Micro-example three: You SWOT your data analytics capability. Strengths: strong technical team. Weaknesses: siloed data systems. Opportunities: new AI tools that could enhance insights. Threats: competitors with better integrated platforms. This SWOT works because you've defined "data analytics capability" with precision.

The difference? In each case, someone made a smart choice about what to analyze. SWOT provided the framework. But the strategic thinking happened before SWOT, when someone said "let's focus on this specific thing."

SWOT needs a context-setting step that SWOT itself cannot provide.

Introducing Wardley Mapping (The Missing Landscape Behind SWOT)

Wardley Mapping shows you the strategic landscape before you choose what to analyze.

A Wardley Map visualizes how value flows from user needs through components to outcomes. It shows what you have, where it sits in the evolution cycle, what depends on what, and where the real strategic questions are hiding.

Here's what mapping reveals:

User needs. Everything starts with what users need. Your map shows this clearly.

Components. The map breaks your system into components—products, services, capabilities, infrastructure. Nothing is hidden.

Evolution. Each component sits somewhere between genesis (new and uncertain) and commodity (standard and predictable). The map shows this positioning.

Dependencies. Component A depends on Component B. The map shows these connections. You see what happens when you change one thing.

The strategic landscape. Most importantly, the map reveals where you should focus attention. The components that are strategic (not yet commoditized) deserve analysis. The ones that are commodities? Not so much.

This simple diagram shows how user needs connect to components at different stages of evolution. Components in the Custom or Product stage are strategic. Components in the Commodity stage are not. Your SWOT should focus on the strategic ones.

Mapping doesn't replace SWOT. It sets up SWOT for success.

SWOT + Wardley Mapping = Better Strategy

Wardley Mapping tells you what deserves a SWOT. Then SWOT deepens the analysis.

Here's the flow:

Step one: Map the landscape. Build a Wardley Map of your context. See all the components, their evolution stages, and their dependencies.

Step two: Identify what matters. The map highlights which components are strategic—custom or product stage—versus which are commodities. Strategic components are the ones that create competitive advantage or represent real risks.

Step three: SWOT the strategic components. Now you know what to analyze. Run SWOT on the components that actually matter. Your analysis is focused and relevant.

Step four: Prioritize action. With focused SWOTs in hand, you can make strategic moves. You know what to strengthen, what to build, what to protect, what to watch.

This combination derisks the entire process. You're not guessing what to analyze. The map shows you. SWOT then provides the framework for deep analysis of the right things.

How To Use SWOT Properly (A Practical Workflow)

Here's a four-step recipe that works:

Step 1: Map the landscape.

Start with a Wardley Map. Don't skip this step. Map user needs, map components, map evolution stages, map dependencies. Take time to get this right. A good map takes hours or days, not minutes. This is your foundation.

Step 2: Identify components that matter.

This is where most people rush. They look at evolution stages and assume Custom or Product equals strategic. That's incomplete.

You need to consider four factors:

External situation and changes.

What's happening in your market? New regulations? Competitive moves? Technology shifts? Market consolidation? These external forces change which components matter.

A component might be in the Product stage, but if the market is commoditizing it rapidly, it may not be strategic anymore. Alternatively, a Commodity component might become strategic if external changes create new opportunities or threats.

Example: Your payment processing is a commodity. But new regulations require custom compliance capabilities. That commodity just became strategic. Or your custom analytics platform is strategic, but a new vendor just launched a product that commoditizes it. That strategic component just lost importance.

What you need versus what you have.

Look at your map. What components are missing? What capabilities do you need that you don't have? These gaps reveal what matters.

Your map shows what exists. But strategy is about the difference between what exists and what you need. If user needs are evolving and you're missing components to serve them, those missing components matter more than existing ones.

Example: Your map shows you have excellent customer support (Product stage). But users now need self-service options (missing from your map). The gap between what you have and what you need makes self-service strategic, even though you don't have it yet.

How your capabilities need to change.

Evolution isn't automatic. Components evolve from Custom to Product to Commodity. But sometimes you need to accelerate that evolution. Or sometimes you need to hold back commoditization to maintain advantage.

Which components are under evolutionary pressure? Which ones need to evolve faster? Which ones need to stay strategic longer? These pressures reveal what matters.

Example: Your custom development process is strategic but slow. Competitors are commoditizing similar processes. You need to evolve your process to a Product stage—standardize it, productize it, make it repeatable—before competitors commoditize the whole category. The evolutionary pressure makes this component critical.

What is most important.

Not all strategic components are equal. You need prioritization criteria beyond evolution stage.

Consider:

- Dependency depth: Components with many downstream dependencies matter more. If it breaks, many things break.

- User impact: Components that directly affect user needs matter more than internal-only components.

- Competitive exposure: Components your competitors are targeting matter more than those they're ignoring.

- Vulnerability: Components that are weak but critical matter more than strong but non-critical ones.

- Transition points: Components at evolution boundaries (Custom→Product, Product→Commodity) matter more because change is happening now.

Example: Your map shows five strategic components. Two are in Product stage, three are in Custom stage. The one in Product stage with twelve dependencies, high user impact, and active competitor attention is more important than the Custom component with no dependencies and low user visibility.

Apply these filters to your map. Components that are strategic (Custom or Product stage), affected by external changes, revealing capability gaps, under evolutionary pressure, and scoring high on importance criteria—these are your SWOT candidates.

Step 3: Run SWOT only on the strategic ones.

Pick the most important strategic component. Maybe it's the one with the most dependencies. Maybe it's the one in the most uncertain position. Maybe it's the one your competitors are targeting. SWOT that one component deeply. Not the whole company. Not multiple components at once. One focused SWOT.

Step 4: Prioritize moves using mapping gameplay.

With your SWOT in hand, use the map to think about moves. If your SWOT revealed a weakness, what components depend on this one? If your SWOT revealed an opportunity, what would need to change on the map? The map helps you see the strategic implications of your SWOT findings.

This workflow prevents the common mistake of SWOTting everything or SWOTting nothing. You analyze what matters, when it matters, with clear boundaries.

Common Mistakes When Using SWOT

Here are the mistakes that waste time and produce misleading results:

Analyzing the whole company at once. Companies are complex. A SWOT that tries to cover everything covers nothing. The matrix fills up with generic statements that don't drive action.

Mixing internal and external factors incorrectly. Strengths and weaknesses are internal. Opportunities and threats are external. But people confuse them. A competitor's new product is a threat, not a weakness. Your brand reputation is a strength, not an opportunity. Clear boundaries matter.

Choosing focus based on politics. Someone suggests focusing on their pet project. You SWOT it to avoid conflict. Six months later, you realize it was the wrong focus. Politics is a poor guide for strategic analysis.

No grounding in user needs. You SWOT a capability without asking "does this matter to users?" The analysis looks thorough, but it's disconnected from value creation.

No consideration of evolution or commoditization. You SWOT something that's already a commodity. Even if you strengthen it, you won't gain competitive advantage. The analysis is wasted effort.

Ignoring dependencies. You SWOT a component without considering what depends on it or what it depends on. You miss the systemic implications of your findings.

These mistakes are symptoms of the same problem: SWOT without context. Wardley Mapping provides that context.

Visual Comparison — SWOT Alone vs. SWOT + Mapping

Here's what happens when you SWOT alone:

You start with a matrix. You fill it with whatever comes to mind. You produce insights, but you're not sure if they're the right insights. The process feels productive, but the output is questionable.

Here's what happens when you combine SWOT with mapping:

You start with a map. The map shows you what matters. You SWOT the right things. Your analysis is focused, relevant, and actionable. The process is longer, but the output is superior.

The difference? Mapping sets context. SWOT provides analysis. Together, they create strategy.

Simon Wardley's Point of View

Simon Wardley, the creator of Wardley Mapping, has a clear position: maps beat SWOT. He argues that we should use maps for strategy, but instead we use SWOT.

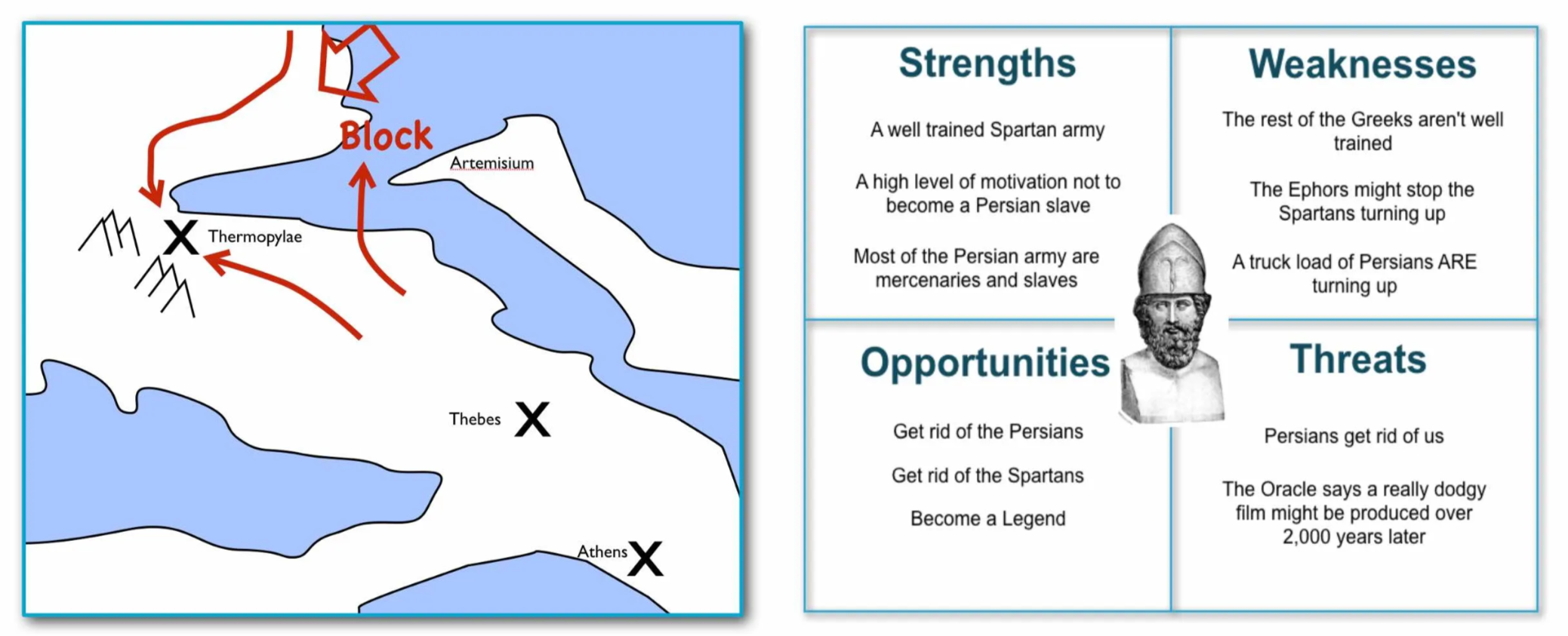

Wardley uses the Thermopylae example to illustrate this. When preparing for battle, would you use a tactical map showing the landscape, positions, and relationships? Or would you use a SWOT analysis with abstract categories? The answer is obvious: the map wins every time.

SWOT is useful only when you have a couple of options to evaluate.

Wardley's point is clear: maps provide actionable intelligence. SWOT provides categories but no tactical guidance. Maps show relationships and spatial context. SWOT treats factors as isolated items in boxes. Maps reveal the landscape. SWOT keeps you in the abstract.

But here's where we differ: SWOT is a very useful tool if applied correctly. The problem isn't SWOT itself. The problem is using SWOT without mapping first.

Wardley Mapping shows you where the strategic positions are—where the Thermopylae moments exist in your landscape. Once you've mapped the landscape and identified those positions, SWOT becomes a powerful tool for evaluating your options. It helps you assess strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats for the strategic positions you've identified.

The key is sequence: map first, then SWOT. Don't SWOT in the abstract. SWOT the strategic positions your map reveals. When you do this, SWOT provides the analytical framework you need to make decisions about those positions.

Wardley's critique is valid: we use SWOT when we should use maps. But maps and SWOT aren't mutually exclusive. Use maps to identify what matters. Then use SWOT to analyze it deeply. This is how SWOT becomes useful.

Final Recommendation

SWOT is powerful when aimed correctly. Wardley Mapping shows you where to aim.

If you rely on SWOT for strategic decisions, the next step is learning how to see the landscape behind it. Don't abandon SWOT. Enhance it. Use mapping to choose your focus, then use SWOT to analyze that focus deeply.

This combination addresses SWOT's core limitation: the risk of analyzing the wrong thing. The map removes that risk. SWOT then provides the analytical framework you need.

The goal isn't to replace SWOT. It's to make SWOT useful and relevant by giving it proper context. Wardley Mapping provides that context.

Tags

Explore More Resources

Continue your strategic thinking journey with our guides, case studies, and tools